Bad Fit

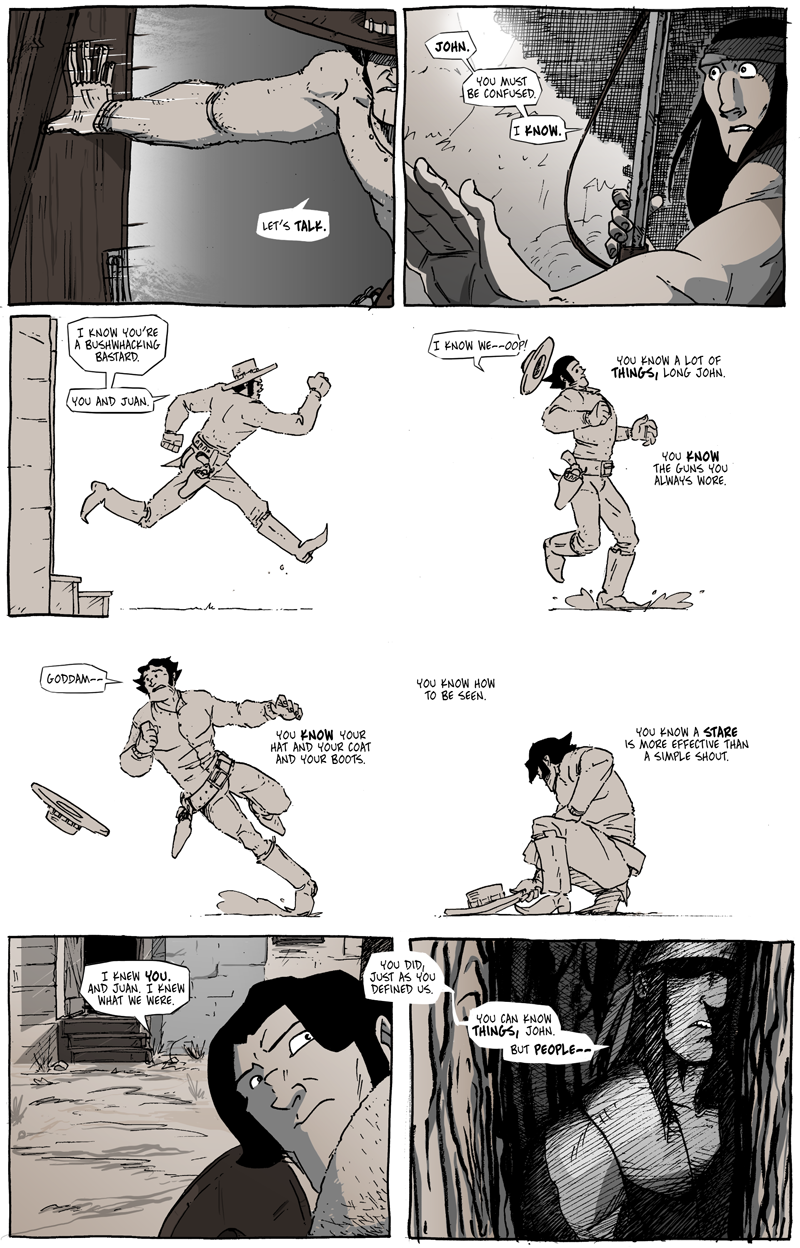

Designing Jonny Mono was a lot of fun, but when it came down to drawing him in the comic, I got caught up in the nuances and ended up doing a lot of redrawing or on-the-page corrections (which was frustrating).

First and foremost, I wanted to stay away from stereotypical designs for Native Americans; I wanted his culture to show through but I wanted the aspect of his character to dominate and not for every frame to shout, “Look! A Native American!” Like I’ve mentioned before, my guiding principles for character design in Long John are all about exaggerated reality, and basically boil down to the following:

- Recognizable silhouette

- Appropriate exaggeration of clothing

- Period-correct attire

- Practicality

I fought so hard to put a shirt on the guy underneath his vest, but the sleek silhouette won out and, when contrasted against the shapes of his lower half, it looked so cool.

The guiding design inspiration for Jonny Mono was to make him look and act like a late 19th-century version of Solid Snake from the Metal Gear and Metal Gear Solid series of video games made by designer Hideo Kojima and published by Konami. Snake’s design is a perfect amalgam of stealthy movement and battle gear which lines up perfectly with his rather cold demeanor despite being neither laconic or quiet. In fact, in the video games, Snake is quite a talker, and I wanted Jonny Mono to be so, too.

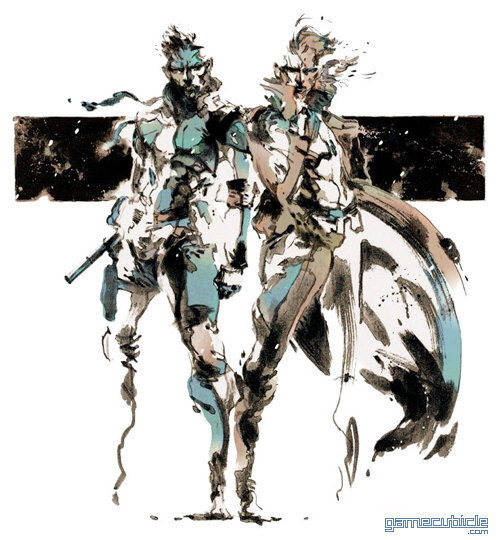

Solid Snake from Metal Gear Solid, art by Yoji Shinkawa

The original Metal Gear Solid game was incredibly inspiring for me as a person in my late teens and early twenties––it was a video game about more than just shooting and killing or about dragons and magic. It’s a game about stealth, you slink in the shadows and try to not be seen. It was a game that asks you to think differently (based on previous, more traditional gaming experiences), to treat your enemies as lives rather than fodder. More than that, Metal Gear Solid was about something, like a good book. For lack of a better term, it had an agenda (for what it was) and whether I agreed with it or not, that a game was trying to do something more than just get kids to spend their parents’ money was impressive and momentous.

Solid Snake and Liquid Snake (not the cleverest of names) from Metal Gear Solid; art by Yoji Shinkawa

More importantly, for the sake of storytelling, Snake’s journey in the game showed me how a good game could be fueled less by overt action and more by waiting and patience. Kojima’s goal, in a sense, was to get players to slow down and consider the entire context they were playing within rather than just blasting and running. To me, that ethic was a perfect description of a character that complements a sort of mousetrap-like personality that Long John is (or was before the night at the lake).

Design sketch of Jonny Mono.

However, I didn’t want him to become a sort of “magical native american,” an idealized, flawless, stereotypical version of a non-white character. Mentor-type characters are necessary in a story, but they do tend to gravitate toward non-white characters. I knew that, even though the upcoming scene would be one of great importance for Long John’s personal growth, Jonny Mono is not the spark to ignite that revelation. Jonny Mono is just a flawed character like everyone else in the comic, and his pure motive in this scene is that he feels bad for what he did to Long John, not to necessarily instruct him and guide him toward a righteous path. That would be too easy and too unbelievable. Besides, Long John has to discover his path on his own; that’s the whole point, after all.

Discussion ¬