The Week – 19 October 2018

WATCHING:

Source: Variance Films

- Until the Light Takes Us documentary

My appreciation for the heavy metal musical genre is not a secret. I don’t admittedly look or publicly play the part of the stereotypical heavy metal fan, but much of the message the genre promotes profoundly speaks to me. That being said, it’s fair to say that the style of heavy metal I listen to the most is fairly mainstream or was: Twisted Sister, Dio, Judas Priest, Metallica, and––most importantly for Long John––the work of Professor Black (Dawnbringer, High Spirits). Sometimes this “classic” metal or “power” metal is jokingly referred to as “dad metal,” and I’m fine with that.That being said, there are subgenres within metal that I have, at least, tried and while I may respect them (most of the time) they were just clearly not something I wanted to listen to. Black Metal––an extreme, low-fi, highly melodramatic subgenre emerging out of Norway and Sweden––is definitely one of those subgenres. It is just not for me.

However, I am also a bit of a true crime fanatic (thanks, mom), and the Norwegian Black Metal scene has seen its fair share of controversy. During the ’90s, I remember the reports of the church burnings and murders attributed to the scene, and this documentary covers that time period in particular, interviewing many of the people involved (including convicted murderers). So, despite being a subgenre that doesn’t particularly interest me, its culture and history were very intriguing. The controversial beginnings of this subgenre have been chronicled in books, articles, and documentaries, but, of them all, one documentary, Until the Light Takes Us, had the highest profile and has always been on the docket to see.

Sadly, Until the Light Takes Us is a bad documentary albeit a very interesting one. I’m not sure what the filmmakers’ intent was, but as evocative and weird as the interviewed people are––as are their values and ideals––the documentary doesn’t problem pose at all. It feels more like a puff piece about these musicians despite barely covering any music. It’s clear the filmmakers are fans, but their idolatry of the musicians is at odds with their making a documentary about the destructive history of the scene. This results in forcing the inquisitive viewer to ask the questions the filmmakers could have asked only to seek answers elsewhere.

image source: Variance Films

For me, the question humming throughout the entire movie is what’s more important in an artistic movement––the art or the movement? The documentary only covers the movement––it’s the story of really angry kids (late teens, early twenties) who are trying to make the most thematically and sonically disturbing music possible. At first, it’s because it’s cool and gives the disaffected a sense of power. Later, as the musicians and fans start to commiserate and find where their personal ideologies align, it becomes something much darker than loud guitars and “corpse paint” could ever be.

It becomes a scene whose music may be about Norse mythology, murder, and the occult, but whose musicians start spouting about racial and cultural purity, homophobia, and militant anti-religious rhetoric. And while they do burn down churches (and other violent acts, such as suicide and murder) and such acts do align with their ideology, it comes across as disingenuous for a few reasons. First, the escalation from back room banter to actual destruction and violence––although rooted in their despondent values––seems to grow less from actually an organized effort to enact change on the world and more from a sense of posturing and one-upmanship. It was all talk for awhile, but as soon as someone actually acted on it, it all snowballed from there. From that we get, second, the only people they seem to be hurting is each other. Aside from one murder of an innocent person and a firefighter who died while trying to extinguish a burning church (the latter death was unintended), all the focused animosity on display in the documentary is toward their fellow musicians for being not legitimate or metal enough.

Their other enemies are general and abstract––Christianity, homosexuals, American influence, trend music. The only enemies that they levy specific machinations against are other bands and musicians who they perceive as “weak”, “false”, or “posing”––accusing them of simply dressing like and playing black metal music without being bold enough to actually carry out the destruction their ethos promotes. Flinging insults of this sort seems to be their main activity because, apparently, just wanting to play music was not enough. Honestly, it is a culture more concerned with gatekeeping than acting on its values, which is the product of being created by angry youths. The musicians who survived these early years lament that the music has become a genre and isn’t as “real” as it used to be, but it’s in iteration that art survives.

While it’s easy to laugh at these people who did all this stuff in their late teens and early twenties for being passionate but myopic, it stops being funny when they start harming and killing each other and, worse, when innocent people die as a result of their misplaced passion, one that overcame the actual art that inspired it to the point that the music became a secondary aspect in the eyes of some of the movement’s leaders. To me, that’s where the cherry gets placed on top of this pie of sadness, and even though I don’t particularly like the music it’s still too bad that it’s the musicians themselves that ultimately made their work trite and unimportant.

READING:

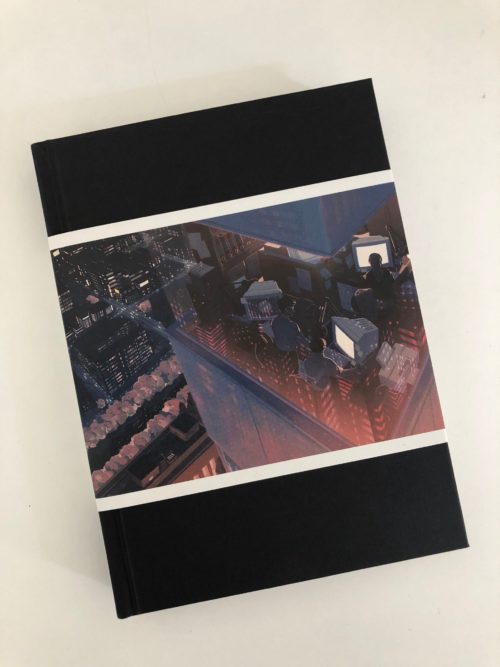

Source: Read-Only Memory

- 500 Years Later: An Oral History of Final Fantasy VII by Matt Leone

In 2014, video game journalist Matt Leone started doing research with the idea that he would create a retrospective look at the creation of the video game, Final Fantasy VII, by SquareSoft (now Square Enix). It was a huge game culturally (it has sold over 11 million copies to date) and literally (the content was spread across three discs for the Sony Playstation) and the move from being a 2D sprite-based game (like Super Mario Bros. in look) to 3D polygonal-based assets was a tremendous leap forward for gaming and the series. Obviously, FFVII was a continuation of the already popular Japanese Role-Playing Game (JRPG) series, of which I was a big fan.

For those that don’t know, FFVII was the seventh game in the series, but only the fourth to be released in the States and was the only accurately-titled game stateside since the first one. Final Fantasy II in the US was actually Final Fantasy IV in Japan and our Final Fantasy III was VI originally. However, Square took a bold step with FFVII by releasing it worldwide as Final Fantasy VII regardless of the number of the last Final Fantasy game you played.

Until that point, JRPGs were a fairly niche genre in the world of video gaming––even the nerds who played video games called those who played RPGs and/or JRPGs “nerds”, and I was one of those super nerds. I had played every stateside Final Fantasy release since the day the first one dropped for the Nintendo Entertainment System in 1990. I loved the deliberate pace of the narrative and the battles, and the need for thoughtful decision-making spread across the convoluted menu systems and relatively simple visuals (rather than a lot of other, more action-based games where you were tasked to dispatch as many enemies as possible by pressing a button as much as possible). When I came around to the Super Nintendo, I played Final Fantasy II incessantly but my fandom became rabid with the release of Final Fantasy III. That game became my personal holy text. So, when Final Fantasy VII was announced for release in 1997, you can probably imagine how difficult I was to deal with as a nerdy, over-zealous fanboy (not to mention it was released a few days after my birthday, so it felt like some weird gift from the universe directly to me).

I obsessed over my playthrough, but in the end I only kind of liked it. From there, my fandom for the series began to wane.

That aside, the game is solely responsible for shifting JRPGs out from its niche into the mainstream. Everybody played it and loved it. In that regard, I was extremely happy. It was a validation of my own tastes and it was nice to finally talk to people about a game series and genre that I loved.

Image Source: Square Enix

Twenty––TWENTY––years later, the game is still talked about regularly and fondly regarded, easily ranking near the top of many “Best Games of All Time” lists without fail. It is a game that will be remembered.

Sadly, the chronicling of gaming history exists in a nascent state with much getting lost to time as people behind great games die or become unreachable. There has been a recent streak to record not only criticism and historical records of a game but also of development. Most importantly, more historians and journalists have begun to reach out to the people who created these games to get their voices on record for posterity, specifically using the oral history format (such records have been made for Bungie’s Halo, BioWare’s Mass Effect: Andromeda, and even in comics with Jim Lee’s Wildstorm Studios) so the history of games can be recorded in the words of the people who made them.

As the scope of research kept expanding to the point where Leone was having conversations with more and more people from the team that made FFVII, it culminated in January 2017 when he published to the gaming site, Polygon, “Final Fantasy 7: An Oral History.” Much like the game it covered, the document was a big hit across gaming culture.

With the piece’s success, Leone and his team crowdfunded a high quality, absolutely beautiful book that collected it along with extra, new material, including a forward written by the creator of Final Fantasy himself, Hironobu Sakaguchi. As you can probably guess, I was among the crowd that funded the publication and, having just received the book (and reading the forward) all I can really say (based on when I read the article back when it was originally published) is that even though I wasn’t the biggest fan of the game itself, it does rekindle the excitement in those memories because it brings new information. It sheds light about a company and a game series, especially at a time when I was a super fan, and treating that information, the series, and even the game with the utmost respect that it deserves.

Discussion ¬