The Week – 17 January 2020

WATCHING:

- One Day at a Time on Netflix

It’s rare that reboots actually work. It’s even rarer when reboots based on decades-old properties actually work well. So, color me completely surprised at how quickly I fell for Netflix’s reboot of the ’70s sitcom, One Day at a Time.

Part of it may be due to my complete ignorance about the original show, of which I only knew the name and nothing about its content or context. In fact, I always thought it was one of the many daytime soap operas based on its name alone. That being said, I had nothing to compare Netflix’s reboot against. Comparing the premise of the new show to the original, however, (thank you Wikipedia) it seems pretty faithful, making changes to appeal more to modern audiences and their sensibilities.

The main reason I like it is because of the outstanding cast and the compelling writing. It does the interesting dance that shows like Scrubs really made popular by easily and believably bouncing between hilarious situations and highly dramatic and emotional scenes in, basically, every episode. The show often brings me to tears with both laughs and emotional resonance.

These jumps never feel cheap or forced, instead spinning organically from the wonderful characters and their relationships with each other.

The story is built around a single mother, Penelope Alvarez, an Army veteran and nurse with two teenage kids––Elena and Alex––and shares an apartment with her widowed mother, Lydia. They are proudly Cuban-American and the show focuses on aspects of being a working single mother as well as her Cuban heritage and the all the space in between.

I actually first heard about the show through the wonderful world of webcomics. One of the developers of the reboot, Gloria Calderón Kellett, is married to one of the elder statesman of webcomics, Dave Kellett, whose works Sheldon and Drive are long-running fan favorites.

More importantly, Dave Kellett has become an ardent resource for aspiring webcomickers through co-authoring the book, How to Make Webcomics, and podcasts like Comic Lab on which he dispenses advice and conversation with fellow webcomicker, Brad Guigar.

Being married to a Hollywood screenwriter, he often talks about the conversations about storytelling, character, and genre that he has with Gloria and it was through his podcasts that I heard him mention One Day at a Time. I only wish, at this point now that three seasons are out and a fourth is on the way, that I had taken that initial awareness to heart and started watching back then; now that I know how good it is, I feel I’ve deprived myself of excellent television for the last few years.

PLAYING:

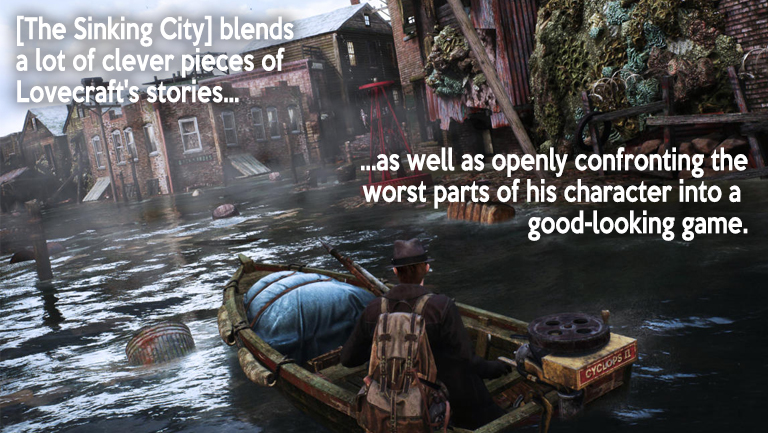

- The Sinking City by Frogwares

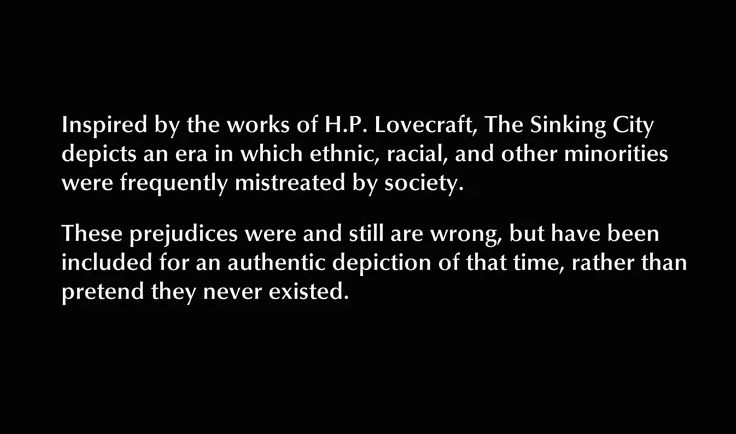

Being a fan of horror writer H. P. Lovecraft can be a complicated thing. His contribution to fiction––especially horror fiction––is undeniably important. However, there is also the undeniable fact that his personal views and beliefs on race and class were appalling (though he did soften a little bit as he got older).

Die hard fans have read the stories, but in terms of public interaction they tend to be split into three groups: one group openly critiques his abhorrent views, perhaps even arguing for his dismissal from canon; another loves the work and just ignores the problems of his biography. The latter group loves the monsters and the lore Lovecraft lightly applied to his stories. This group rabidly consumes the spinoff Lovecraft media like the video games and, most popularly, the The Call of Cthulhu tabletop role-playing game, among other things like Cthulhu plushies, “Lovecraftian” music, and general creepy imagery awash in cult symbology, body horror, and dripping tentacles.

I would like to believe I am a member of a third group, one which openly loves his stories and that fully acknowledges his racism, sexism, and classism. More importantly, we acknowledge that his views fully inform his stories. Best described by writer China Miéville in the excellent introduction he wrote for a Modern Library edition of Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness, he wrote that when we closely examine HPL’s monsters we can actually see that they aren’t just the product of a highly creative mind, but they are actually creative manifestations of his xenophobia and racism. To me, it’s more interesting to examine Lovecraft’s work on this level––and, further, to examine his focus on knowledge, sanity, and religion––than to either just talk about what a reprehensible person he was or to just read stories about detectives-heroes fighting gigantic eldritch monsters. All of these things are equal and connected parts of the conversation about H. P. Lovecraft.

What makes Lovecraft’s work stand out to me is that the horror is not about grossing you out or scaring you in the text itself. It’s a horror that comes with rumination––sitting back and thinking about the implications of the story after reading it. It’s a focus on terror rather than horror.

As I alluded to, a lot of what we call “Lovecraftian” fiction seems to just take his monsters out of his stories and have humans defeating them or getting defeated by them––a group of plucky investigators find a cult trying to end the world and it’s up to the heroes to put a stop to a ritual or something. However, that type of story really only exists in one of Lovecraft’s tales––”The Dunwich Horror“––the rest are just about humanity intersecting with information on a cosmic scale and the fallout from that intersection.

All of that is to say that Frogware’s detective game, The Sinking City, is a piece of Lovecraftian fiction that really “gets” what I love about Lovecraft. It’s not an action power fantasy. It’s not jump-scare gorefest. It’s about learning and dealing with the threat of the information you find.

It’s not perfect, but it’s impressive and I’m enjoying the hell out of my time with it. The game plays out like it was made for the type of fan I am, blending a lot of clever pieces of Lovecraft’s stories as well as openly confronting the worst parts of his character into a good-looking game, capturing the existential dread and exhaustion that permeates the story it borrows from most, “The Shadow Over Innsmouth.”

Most impressive, though, is that it is doing something novel with not just Lovecraft’s stories but also his values, something that I’ve only really seen done well in fiction in the last five or so years with things like Victor LaValle’s The Ballad of Black Tom or Ruthanna Emrys’ Winter Tide. It’s exciting because it’s not revisionist––rejecting Lovecraft because he was a jerk––and it’s not power fantasy adventure storytelling––a direct opposition to the stories Lovecraft wrote. Instead, The Sinking City is something better than both––a Lovecraft story that embodies the things that defines what he did in his fiction and uses them to tell new stories that fit into his work like a puzzle piece and shine a brighter and better light on the body of work as a whole.

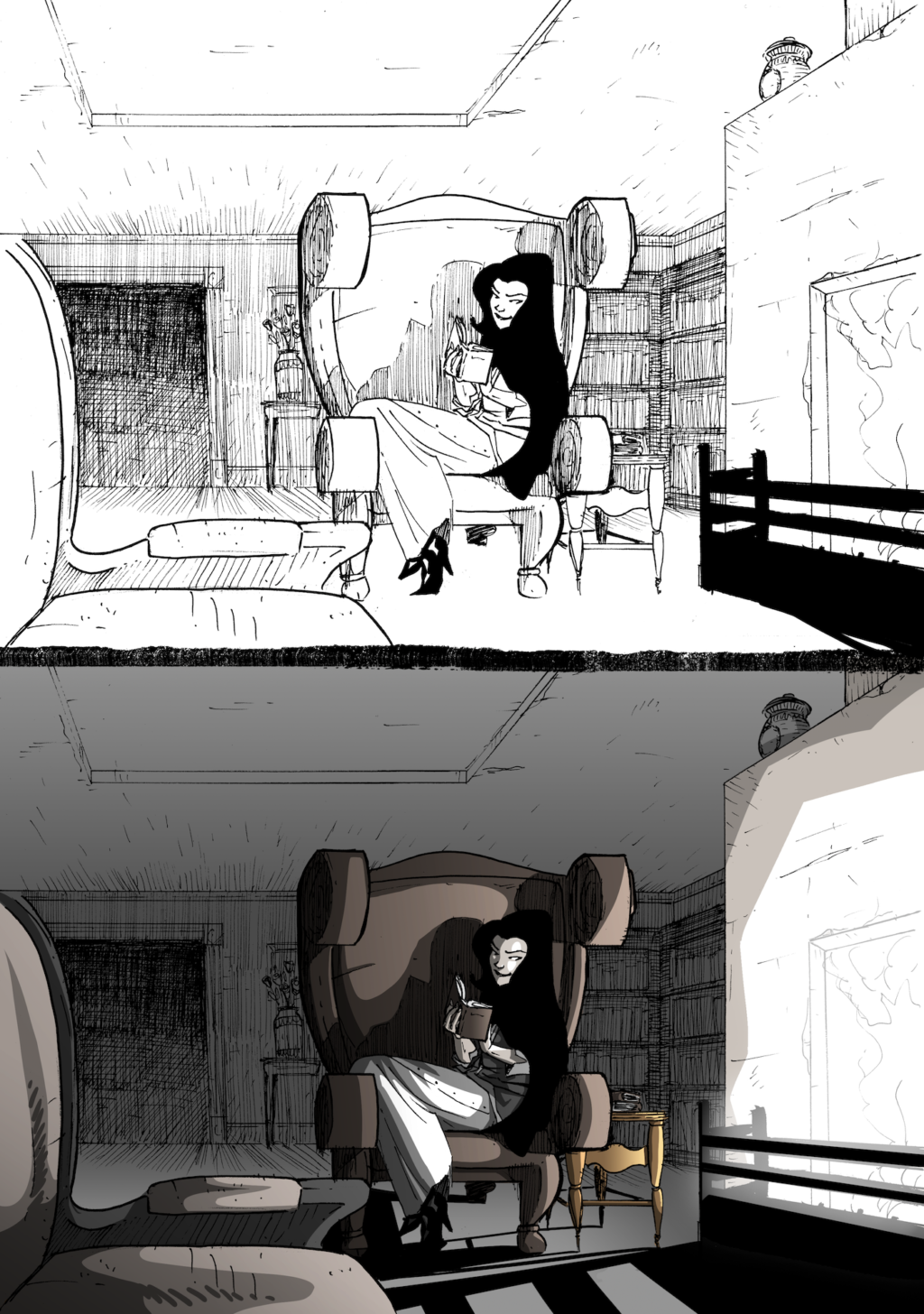

LONG JOHN CHAPTER 4 UPDATE:

I continue churning away at Chapter 4. I’m making good progress on the coloring of the book, so I plan to start getting the pages ready and setup for publishing to the website sooner rather than later.

As for the book, again, I’m waiting on a few factors to come together in terms of extra content. Volumes 2 & 3 were kind of light on extra content and with this volume starting the next piece of the story, I kind of want to make sure it’s packed with good and substantive stuff. So, not since Chapter 2 have we published first to the site and then made the book available, but I think that is the best way to go for this chapter and for the book, in the long run.

But still, coloring is slow.

–––––––––––

Another aspect of this that has slowed me down is that I had a mild existential dilemma (speaking of Lovecraft) with regard to lettering the book––placing the text on the pages themselves. I’ve basically lettered the book from scratch two and a quarter times.

When I say “lettered,” I don’t mean re-writing. The words are all the same, instead it’s about placement in panels and and on the page.

Because of a scene early in the book, I became hyper-aware of the rhetorical value of good lettering. Just as with everything in the art, the lettering, too, guides the reader through the story in more ways than one. Lettering, of course, indicates who is speaking. It can also indicate the tone of the line of dialogue. How you break up dialogue can speed up or slow down the reader. Backing away from the book, it becomes clear that dialogue placement also guides the reader’s eyes. You can use lettering to make sure the reader sees the things in the art you want them to see.

As with any interaction with theory, it can become easy to spiral out of control. Needless to say, I’ve learned a lot about the art––and it is decidedly an art––of lettering comic books with this volume. I’ve come to really respect the folks that do this type of art for a living (and may be something I hire out for in future volumes).

For those interested in lettering and the theory behind it, I can’t recommend Richard Starkings’ book, Comic Book Lettering: The Comicraft Way (despite the weird cover) and the aggregated lettering tutorials that letterer, Nate Piekos, has compiled on the Blambot website. It’s really interesting stuff.

Discussion ¬