Mistakes Were Made

I haven’t read a lot of manga, but as I was developing Long John and taking in influences outside of the animation that fueled my previous comic, I turned to visual inspirations that were, mostly, outside of my wheelhouse: European comics (aka bandes dessinées) and manga (the Japanese word for comics). Again, the main inspirations were the creators (writers and artists) behind the Image Comics’ Prophet reboot (Simon Roy, Giannis Milonogiannis, Brandon Graham), Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo, and detective fiction, but I was gaining a keen interest in comics, specifically, and wanted to see what else was out there beyond the Marvel/DC dichotomy that rules the status quo. Part of that was because it all looked the same (as much as styles can vary, there is an overall aesthetic to American superhero comics that permeates originality and my eyes get tired walking past the shelves of tights, muscles, blood, and boobs), but another part was because I finally began to kindle a love affair with the medium itself, and I wanted to dig into the art that is “making comics.”

So, I dug into work by Enki Bilal and François Boucq; their tactile styles really show, for lack of a better description, the paper and ink as much as the lines they comprise. Their work feels like handmade art, and I loved it because, even if it was work from the 1970s and 1980s, it felt so new.

But, for style I found inspiration in Takehiko Inoue’s Vagabond, which I’ve briefly discussed before with regard to his willingness to shift inking styles and approach simply for the sake of the emotions of the scene. Though his comics can’t claim linear consistency, there is a consistent quality that underlines the entire work, from story to character design to how he uses this variety of styles.

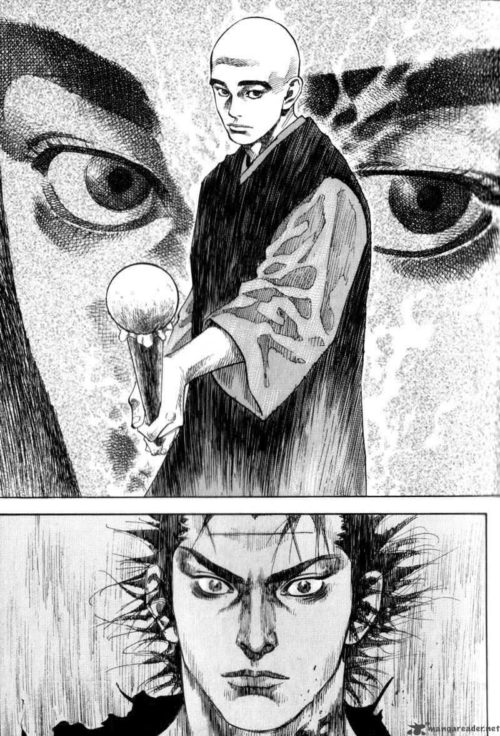

A major factor that I’m bringing into Long John starting with this page is inspired by Inoue’s gleeful shifting between realism and expressionism (to an extent). That is, how liberally he presents the comic, bouncing between highly realistic art (meant to accurately represent the real world) and incredibly figurative art (showing things that other characters likely don’t see but express something more than simply “reality”).

One way he does the latter is to play with the line quality and medium; no doubt the characters don’t suddenly see a shift from a realistic character to one thickly outlined by visible dry brush strokes, for example.

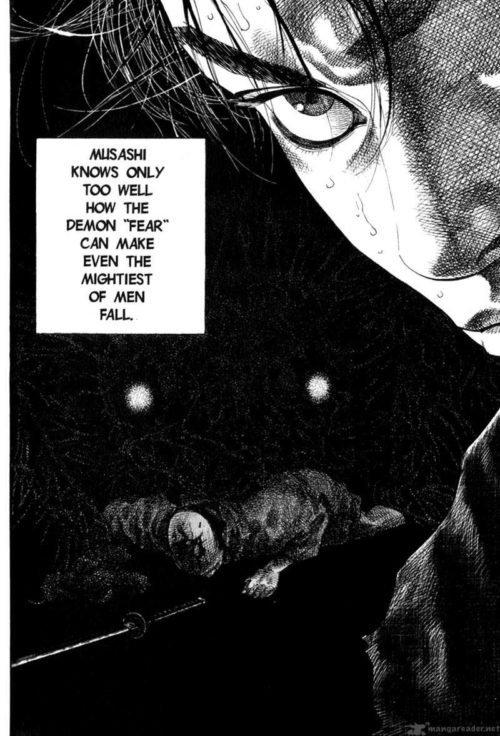

Representing fear as a demonic entity, bright eyes shrouded in hatched darkness.

The basic story of Vagabond is that it’s a fictionalized biography of the famous ronin swordsman, Miyamoto Musashi, who, as a brash young man named Takezo, realizes his talent with a sword and decides to go on a quest to become “indestructible.”

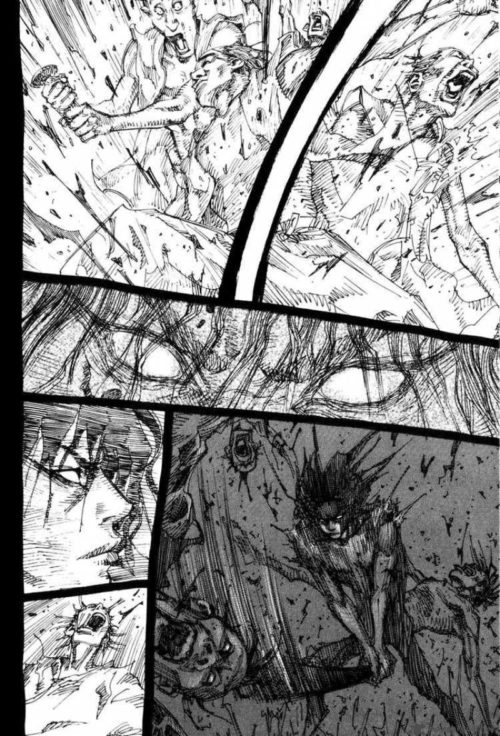

Takezo is, however, haunted by a lot of death in which he was either involved or directly caused, and this repressed darkness sometimes gets the better of him. When it does, Inoue represents it in the comic in very sketchy lines, incredibly exaggerated action, and grotesquely deformed proportions.

Things get weird (and violent) in this otherwise highly realistic comic.

I wanted do incorporate something like this in Long John, especially regarding the internal conflict between his old way of thinking––his arrogance and entitlement––clawing to take his mind back over. Basically, it’s “the rot” that Hellrider Jackie warned about way back at the beginning of the comic. It’s strictly figurative and not something that exists in the world itself. Perhaps it’s a step too far, but it’s a step I’m willing to take.

Discussion ¬