Sketch Fridays #24 – After Darwyn Cooke

For any creative, new expressions are the sum of their influences. We are all products of such algorithms, asserting our independence while hoping the seams don’t show. The tautology of this tendency is hilarious: you can’t show your influences unless you have influences.

There is a strong, post-modern, self-aware streak coursing through popular culture as of late in films and video games and television shows, etc., all of which beg the audience to look at the very seams we work so hard to shelter from prying eyes. I think such turns come when we accept our confidence in our abilities and aren’t afraid of being called frauds anymore. Such confidence was on display in the successful superhero-parody, Deadpool, or recently in the Chip Zdarsky and Joe Quinones reboot of Marvel Comics’ Howard the Duck comic series. They beg the audience to draw the lines between inspiration and the inspired, they’re proud of it and flaunt it.

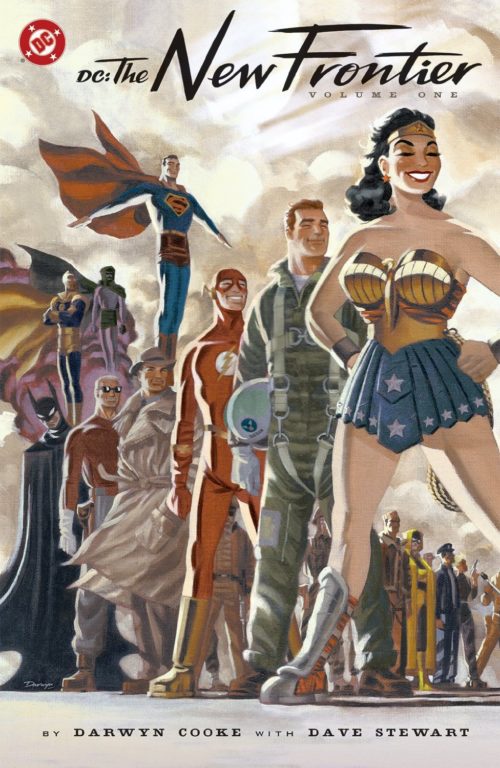

In a subdued way, artist Darwyn Cooke was the same, but without much pretense. Cooke was an artist that most people in my age group have encountered despite his name never being forward-presenting. He was a freelance storyboard artist on Batman: The Animated Series, and, later, handmade (with the help of computers) the very stylish opening credits to the highly regarded animated series, Batman Beyond (as well as a stellar short in celebration of Batman’s 75th anniversary). He redesigned Catwoman back to her cat burglar roots in the early 2000s (and made her outfits a bit more practical and, at the very least, stylish). Cooke also made the Silver Age of DC Comics cool again with his hugely influential graphic novel, Justice League: New Frontier.

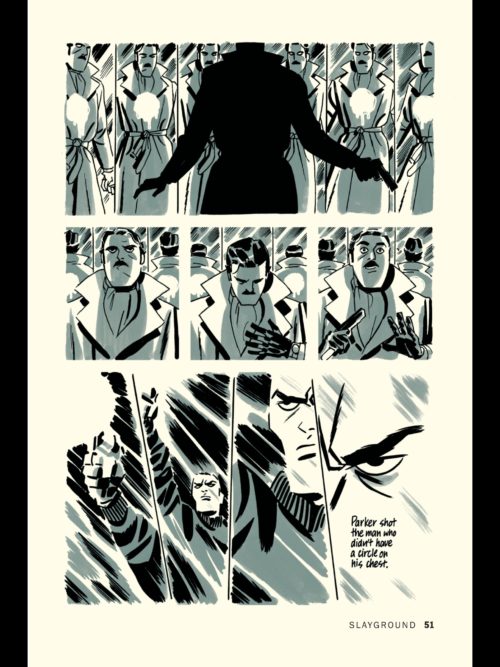

For me, his series of graphic novel adaptations of the Richard Stark (a pseudonym for novelist Donald Westlake) gangster revenge series of books featuring the singularly-named Parker played a huge part in my developing style, especially for Long John. Some may be familiar with filmic adaptations of the first book in this series––The Hunter––in 1967’s Lee Marvin vehicle, Point Blank, or the 1999 Mel Gibson vehicle, Payback. With such a diverse catalogue, it’s clear that Cooke was less interested in showing off how good he was at making the old new again as he was in telling a story in the best way possible, no matter the medium.

Cooke’s influences were clear but he wasn’t a mere retro stylist who reveled in the tropes and irony of doing such a thing (Quentin Tarantino dances dangerously close to this line). Instead, he was a creative that kept his head down and used his highly unique and comfortable style to draw the audience in through its embedded nostalgia while delivering a well-crafted and modern story on top of that.

When I learned that Cooke died on the 14th, the news deeply saddened me, more than I expected. I wanted to write this much earlier, but I had trouble finding an angle that was more than just pathos or navel-gazing. With that, I still have only crafted what dozens of people have already done online by fashioning a superficial retrospective. The best I have to say is in the drawing at the top where I attempted to draw Long John in Cooke’s style. The result made me laugh because it’s actually not too different from how I normally draw him, which speaks much more loudly than any word I have written here.

I have never been quiet about his influence on Long John––in everything from the sharp jaws of the character design to the Parker-influenced coloring I landed on––but I hadn’t realized how important his work was to me until he died, which is the saddest part. His work was more than just a seam that kept my art together, but also a pattern on which I have cut my cloth.

Discussion ¬