The Week – 12 November 2021

LISTENING:

- Long After Dark by Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers

In the summer of 2020, my great Queen listening journey came to a close. It was an invigorating task to listen through a band’s extensive discography on a monthly basis from start to finish. I honestly never thought I’d make it through the entirety of Queen’s catalogue, and when it ended my first thought was, “that was fun,” before thinking, “that was easy.” The last thought I had was “who’s next?”

My Queen journey started because I was challenged as a “real” fan of Queen. However, even by my own metric I wasn’t one; so, I figured I’d make myself one or not. Now that task had ended, I figured I’d reflect on any other musicians I claimed allegiance to but, when inspected closely, I didn’t actually have a strong grasp on. Though a few bands came to mind, I settled on the challenge that I figured would be the most fun: the discography of Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers (with the solo Tom Petty albums shuffled into the mix).

As of this writing, I am at the tail end of his sadly shortened (but very long) career with a mere two albums remaining: the Heartbreakers’ Mojo (2010) and Hypnotic Eye (2014). Overall, though, bouncing through his catalogue has been a more muted affair than it was with Queen. Queen relished in experimentation and musical diversity, mostly emboldened by the fact that it was a band comprised of four unique songwriters.

Tom Petty wrote every song in his catalogue (with only a few exceptions––a lot of co-writes and very few covers), so there isn’t a lot of surprise along the way. The worst comment I can make about an album is that it “sounds like a Tom Petty album.” Before I attract undue ire, Tom Petty’s worst is better than many bands’ best.

Even with the albums I haven’t cared for as much, they are still packed with jangly guitars and hummable melodies that dig into your brain, popping back out when you least expect them to. Bland or rocking, profound or superficial, Tom Petty never really wrote a bad song, and that is what comes through the most as I walk through his career. But there is a sameness which has colored some listening experiences, even though it has me tapping my foot with every song along the way.

As I near the end, the album I keep coming back to is 1982’s Long After Dark, his fifth album that capped the end of the hot opening stretch of his career (it slumps for a little bit before roaring back with Full Moon Fever, his first solo album). It’s not that it is especially better than other albums from this first run, but, to my ears, it’s the most solid front-to-back album experience with an incredible run of amazing songs in the middle of it. While other albums may have better songs (and more successful songs) and this album may have one major clunker (sorry, but “You Got Lucky” is not good), Long After Dark is the textbook definition of the opening era of the musical persona called “Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers.”

WATCHING:

- The Harder They Fall on Netflix

I certainly don’t include myself in the mix at all, but after a long dormancy, it seems––in small, quiet steps––westerns seem to be edging back into the public sphere. With the triple threat of HBO’s Deadwood, Rockstar Games’ Red Dead Redemption, and Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained straddling the opening decade of the new millennium, all three presented unique, different, and distinctly modern approaches to a genre that many considered tired and dried out. The best part about all of those examples is that while they feel modern and new, there was no denying their classic western influences which they all wore on their sleeves (especially the latter two).

Since then we’ve seen entries like Netflix’s Godless (which was only okay), Rockstar’s triumphant return with the sublime Red Dead Redemption 2, and the Coen Brothers’ outstanding adaptation of True Grit (not to mention their bizarre but fun Netflix anthology film, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs), all of which speak to a healthy heartbeat for the genre.

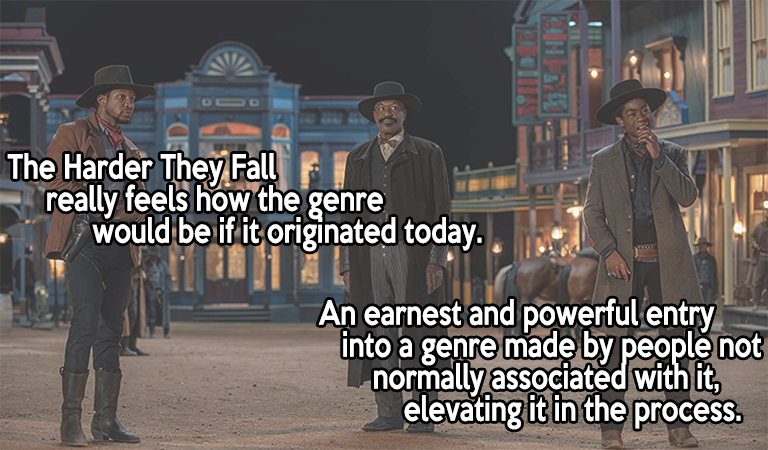

Netflix continued the lifeline with their recent release of The Harder They Fall, directed by British musician and filmmaker, Jeymes Samuel, and starring a bevy of amazing talent: Idris Elba, Jonathan Majors, Regina King, Delroy Lindo, and Zazie Beetz, to name a few. Together, they created an incredibly stylish, stylized, and modern take on the Spaghetti Western. Of course, all the previously mentioned titles (with the possible exception of Deadwood) all scoop from the Spaghetti Western pot, but The Harder They Fall really feels how the genre would be if it originated today. The colors are bright and coordinated. The gun fights are romanticized, stylish, and over the top. The characters are arch and easily readable. This film is pulp fiction in its truest sense. It’s an earnest and powerful entry into a genre made by people not normally associated with it, elevating it in the process, which is the heart of what Spaghetti Westerns did in the ’60s.

What makes it stand out is that the majority of the characters in the film are all based around real people: Bass Reeves (probably the most well-known of the bunch), Nat Love, Rufus Buck, Bill Pickett, Stagecoach Mary, and a bunch more. However––and it can’t be impressed enough––this is not a historical story by any means. But it doesn’t matter. True or not, it’s bringing attention to legitimate badasses of the wild west, elevating their names to a higher platform in pop culture that they surely deserve (seriously, look up any of those names and just read at how unequivocally badass all of them are) but have been denied such attention due to being black at a time when the exploits––both as heroes, anti-heroes, and outlaws––were not recorded nor capitalized upon like their more famous white colleagues.

What The Harder They Fall does, though, is focus on being the most awesome and fun and action-packed western they could possibly make, and they did so with aplomb. Historical or fictional, traditional or progressive, this movie was so much fun from start to finish.

CHAPTER 5 UPDATE

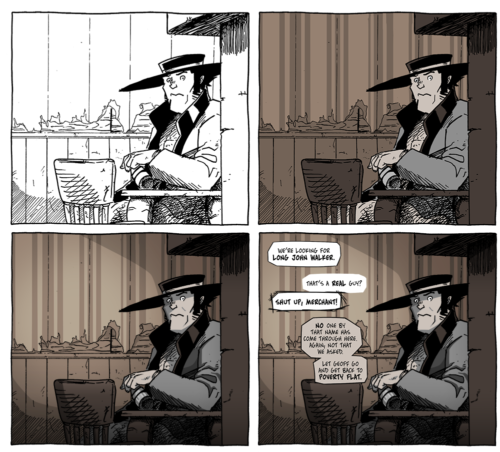

As of this writing, all of the lettering is done for Chapter 5. That means the script is locked down and all the dialogue and captions have been digitally added to the art. This also means that most of the dialogue also has word balloons behind them, save the few where I want to see how the coloring of that panel turns out first.

What comes next is the two-phase process of coloring.

Phase 1 is called “flatting” which means going through the pages and dropping flat colors in each panel––the most basic coloring. What this does is separate the elements of each panel from each other––characters, foregrounds, backgrounds, props/items––by giving them distinct or different colors which will make the next phase easier.

Phase 2 is shading and highlighting. With the flatting done, I then go back through the pages and start “rendering” the images: adding shadows and highlights on the figures and backgrounds and anything else that makes them look like the comic exists in a bit more of a believable and fully realized world.

Flatting is the part I look forward to the least; it’s tedious work, but it’s necessary work. It’s best to do all the flatting first and then go through and do the shading because otherwise every page would take forever and I want to feel, at least, like I’m continuously making forward progress.

There are some art corrections I want to make and even some other things I want to/need to draw to really flesh out the book. So, there is still quite a road to drive down, but the hardest work is over. Now the boring drive straight down the long, empty highway begins. At least the destination will be nice.

Discussion ¬