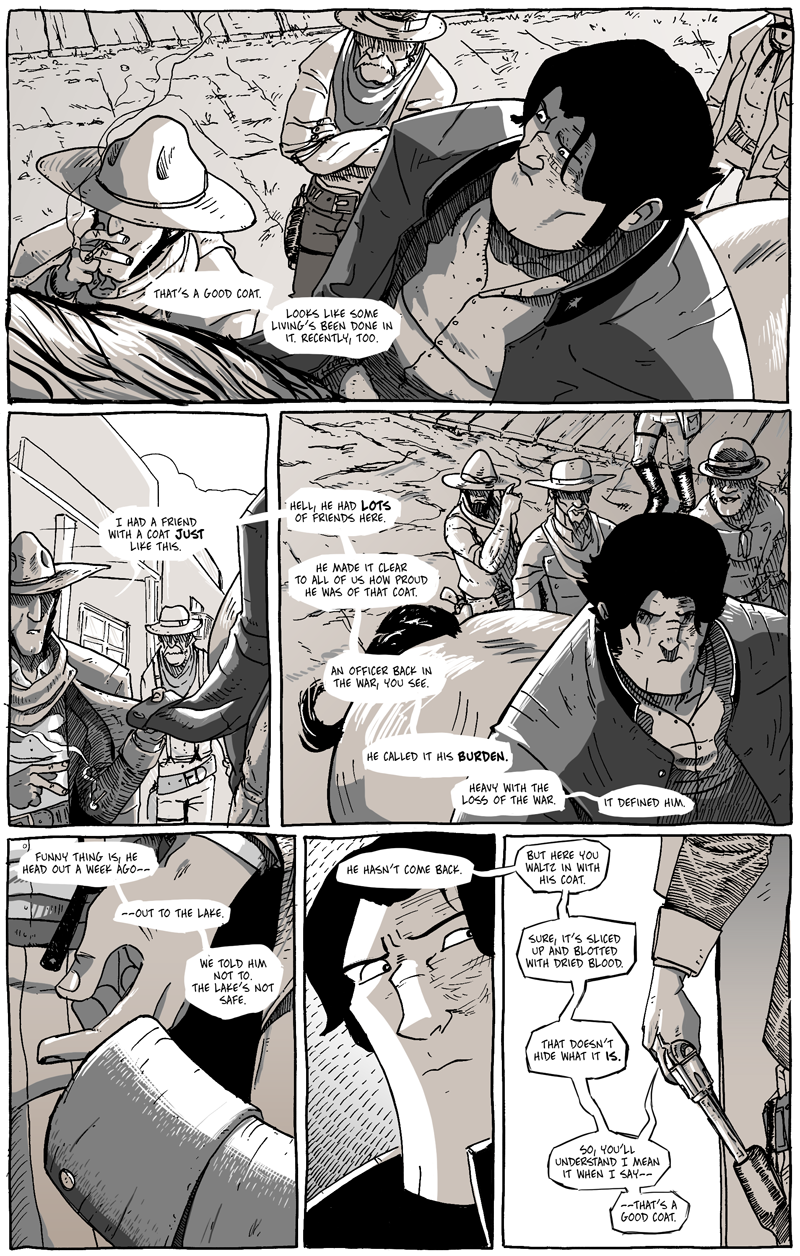

A Good Coat

Essentially, no matter the method of distribution (though I specifically mean print and web), the process of writing comics is essentially the same. Page sizes may vary, but ultimately––in the case of story-based comics––a comicker tends to have a uniform amount of space for a page and the goal is to tell a satisfying amount of story within that space. However, because comics on the web and print comics tend to be read (in the creator’s mind, at least) at different rates, some smaller, more subtle, aspects of the writing process change.

The goal of any page––be it print or web––is the same: to give the reader a satisfying experience and to get them to want to see the next page. The way I heard about the page-to-page “cliffhanger” was through Will Eisner (1917-2005); a comicker in his own right––he created the pulp hero, The Spirit, and is credited as well with promoting the idea of “graphic novels” with his 1978 book, A Contract with God––Eisner was also one of the first thinkers (and teachers!) of comics. Eisner talked about comics with a nigh-academic attention to detail (to boost comics’ academic credibility, Eisner was also the first to suggest they be called “sequential art” rather than “comic books” when discussing theory), which mostly means he took not only comics, but their creation, as seriously as a novelist does her work or a painter his. What this line of thinking includes is the creative, fun, expressive stuff, but it also includes the rhetorical, technical, design stuff that many professionals in their fields think about––these are the things that, to the reader, make the medium “look easy.” It looks easy because the artist has thought out (in the case of comics) each page, each panel, each dialogue balloon in the singular, as well as how they all connect to each other, creating a holistic experience.

For comics, Eisner suggests the page-to-page cliffhanger (he wrote about it in his book, Comics and Sequential Art, originally published in 1985) as an essential quality of making compelling comics. The idea is that every page should end on something that will get reader to want to turn the page, not to turn the page simply because it’s a book and that’s what we do while reading books. With that in mind, creating a comic book page is more akin to poetry than prose because you’re working within a defined space and, like the narrative arc of storytelling, that page itself must have––in a sense––a beginning, a middle, and an end. That end, however, should not be a denouement as much as it should be a tease or a question, one that will be answered with a simple page turn.

While initially laying out Long John, I crafted the pages to work like that––as any good comicker does (or so I tell myself). However, Long John is primarily a webcomic, which, by definition, is different from a print comic. While it’d be easy enough for me to ignore that difference and just post the comics as they were written, I must keep in mind that reading a completed book is not the same as reading two pages a week, and that there is a day-long gap between the two pages each week, and a five-day gap between the pairings. So, in short, reading Long John on the web is a much slower reading experience than it will be in print.

What that means is that the enticement between pages must be stronger and bolder than it needs to be in print, yet––because of the length of time between pages––each page must also feel like a complete and satisfying experience.

So, for Long John, there will be differences between the web version and the ultimate print version. Because actually changing art would be too time-consuming and could possibly throw the whole thing off, the only way this will really affect the comic is through dialogue dispersal.

With this page, the print version will have the last bit of dialogue––”–that’s a good coat.”––will be moved to the top of the following page, if only because I feel that the enticement of “What’s he gonna say?!” can work as a page-turn mechanic for print much more than the web, because no one will be willing to care about how that sentence is going to end two days (or, in this page’s case, five days) from now. The actual enticement for both cases is, “Oh crap, he’s drawing his gun! What’s he going to do?!” but, with the displaced dialogue, it’ll help to get that reader to turn the page even faster.

Yes, all this thought and subsequent post over where to put four words.

Discussion ¬