Proving Grounds

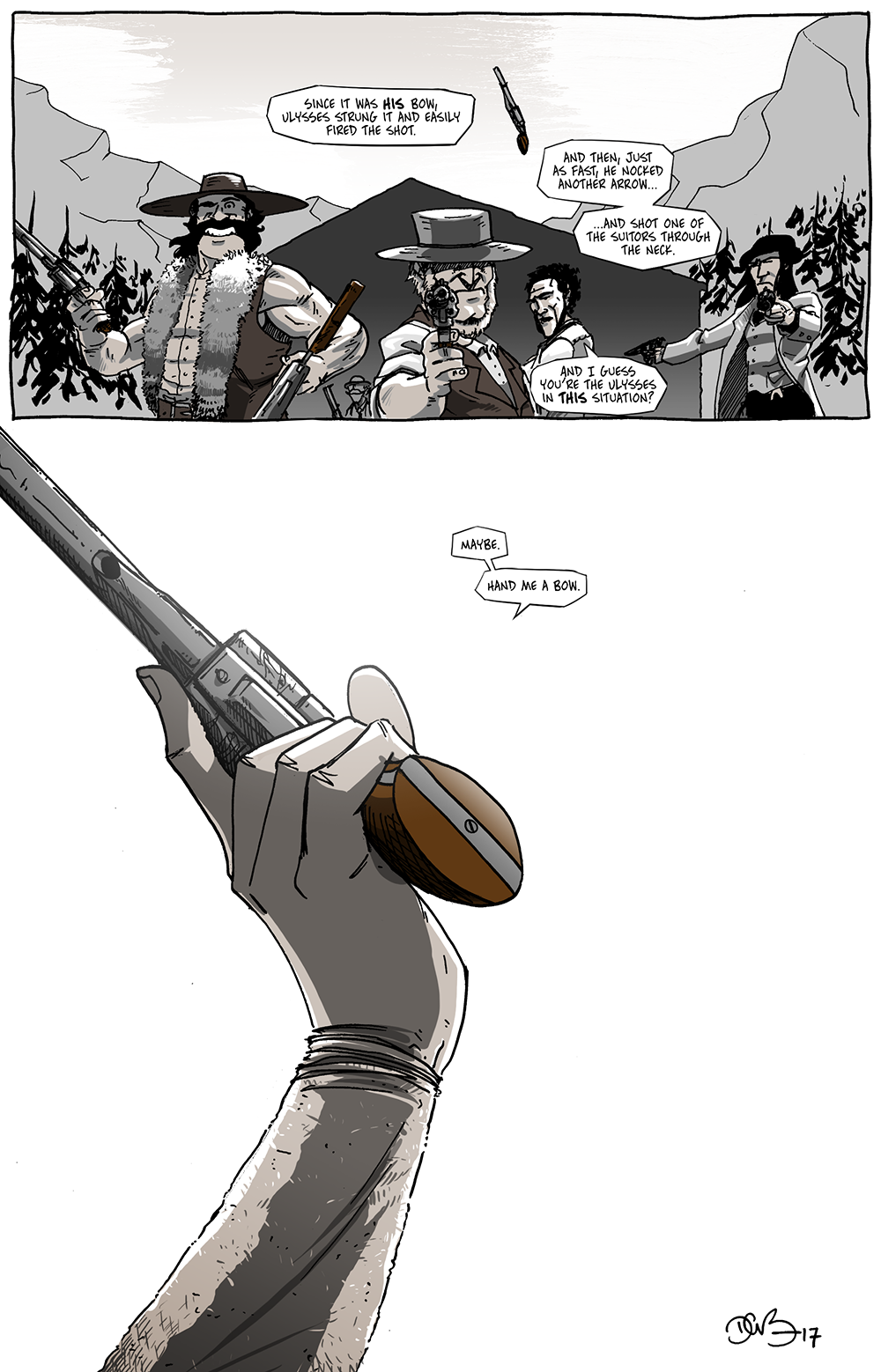

If you follow the website, the comic’s Facebook page, or me on social media, this page will come as no surprise to you as I used the second panel in much of the marketing for this chapter.

––––––––––––––––––

I’ve been thinking a lot about where drawing begins for people, for me. Whether it has been through the administration of some artistic mentoring opportunities this summer as well as talking about how I started drawing and making comics in a few recent interviews, a lot of the conversation has not––fortunately or unfortunately, I don’t know which––focused on my more mature inspirations (Jeff Lemire, the recent Prophet reboot, Darwyn Cooke‘s Parker series) and instead focus on the comics I walked away from when I became a more advanced artist. Those abandoned comics were the ’90s X-Men and early Image superhero comics, the ones that got me into reading comics but, a few years later, made me walk away from them for the same reasons they attracted me: they were bombastic, shallow, action-packed testosterone power-fantasy and, like listening to loud music for hours on end, I eventually got numbed to it and wanted something more subtle and substantial.

While I have since gone back into the archives and re-read those comics and dove into the archives before I arrived in the early 1990s, I really can’t attest to their influence on me aside from being so vivacious that they sparked the desire to draw in the first place. They were the catalyst, but are not the fuel.

My artistic catalysts, though not my artistic fuel.

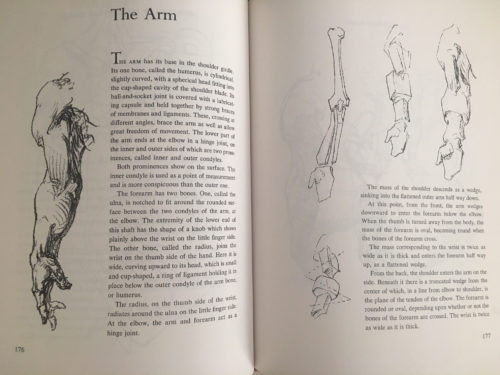

That said, my thoughts have been guided back to those books recently and even though I don’t find much artistic value to them (aside, really, from X-Men: God Loves, Man Kills, which is still brilliant), I do hold them close. They definitely got me into drawing, but they didn’t really teach me how to draw. They were oversized suits I tried to fit to my frame, but I didn’t know how to tailor, so I wobbled and fell, but they gave me a goal to reach in my early days. If pushed to find the single step that took me from eager fan to (the beginning of) a serious student of drawing, it could actually be narrowed down to just one book: Bridgman’s Complete Guide to Drawing From Life by George Bridgman.

My old and heavily annotated copy of Bridgman’s book.

Admittedly, there is a connection between this book and those early comics. I hunted for the book after hearing my early artistic idol, Jim Lee, mention the book as the quintessential text for his development as an artist. That recommendation was good enough for me, and I committed all of my resources to finding it. When I did, and subsequently devoured it and let it stew, it turns out his recommendation was exactly what I needed.

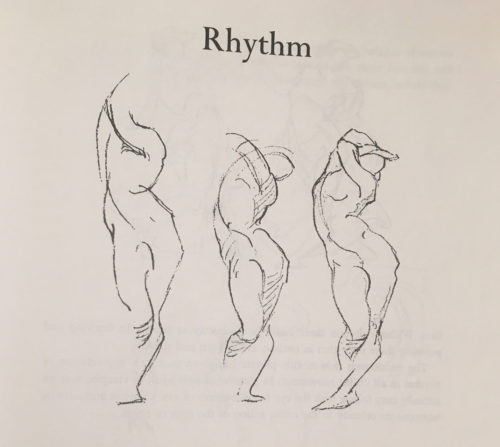

Bridgman’s emphasis on form and movement were a very different approach from what more traditional instructional art books used.

Most figure drawing books are in the vein of Burne Hogarth––an astounding artist in his own right––but those books are very classical. All the drawings look, for one, finished but, aside from that, they look like Greek statues rather than living figures in motion. In fact, they look very inert, albeit powerful and beautifully rendered. Bridgman uses a very different ethos for his book. His drawings look like sketches. They’re not step-by-step––they look like a sketchbook page: a collection of doodles that look like they were done during a conversation explaining how to construct a hand, for example. They, for lack of a better word, look practical and useful, the quick expressions pulled from the mind of a working illustrator. Because of that loose, sketchy approach he took with his illustrations, the results felt, at the very least, much more attainable than anything I could glean from a Hogarth book, which felt more like an anatomy textbook than an inspirational how-to-draw book (for me, at least).

To boil it down, Bridgman’s basic pedagogy was to look at the body as forms and masses rather than individual muscles and pieces that weave together. In talking about Bridgman, Jim Lee once said (and I’m paraphrasing), “Knowing the names of all the muscles in the arm doesn’t make you a good artist. It’s knowing how they work that matters,” which is actually the most concise description of Bridgman’s book. Actually, I found the exact quote from the video I saw in the ’90s (click play below to go right to the quote and his mention of Bridgman which started this whole mess for me):

Looking at his focus on form and movement, I think you can see the clear line from this book to how I draw; I honestly can’t think of a more impactful work on my ability (including any class, video, mentorship, etc.), especially in the face of those early ’90s comic books. While those comics certainly opened up my imagination and inspiration, there certainly wouldn’t be a Long John (or it certainly wouldn’t be as good) without Bridgman’s book.

Discussion ¬